In Santa Clara, a woman creates a shrine in her dead husband’s bedroom. His belongings and her favorite dress are carefully displayed around the room. On the bed lies his photograph next to a framed picture of Jesus Christ.

In Cuba nothing is ever quite as it seems, and religion is no exception. At first glance, Catholicism seems to reign supreme. The signs are all there; you can’t walk three steps without encountering Our lady of Mercy, Saint Anthony or Our Lady of Charity; the Pope himself visited in 1996 and every small town is centered around a church.

Yet scratch the surface and it’s not Our Lady of Mercy thats smiles through the grime, but Obatala the Creator.

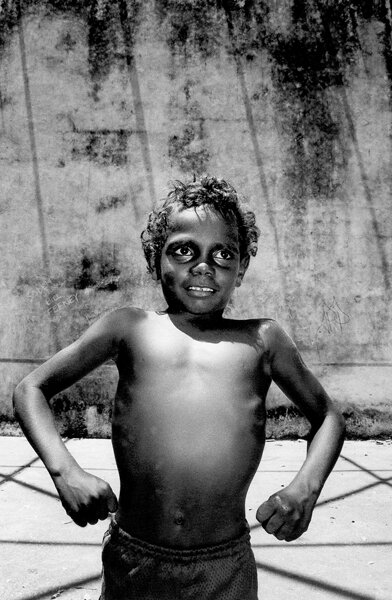

Santeria, or Regla de Ocha, is the main religion practiced in Cuba today. Dating from the early 16th century, when the slaves hid their true African beliefs behind the safety of the Catholic veil, it is essentially a combination of the religious practices of African slaves and Catholic iconography.

Catholic saints are associated with Orishas: the Santeria gods or ancestral spirits. If the Saints glorify an unobtainable perfection; the Orishas represent human frailty and weakness, a form of guilt-free accessibility the sinners in the confessional can only dream of.

Each Orisha is associated with a colour. Thus the mighty Obatala is pure white. Neustra Senora de la Merced, goddess of the underworld, mother of all Orishas is a subterranean blue. Each colour represents different qualities of the earth and followers align themselves with colours according to a priests readings. Witchdoctor Calidad wears a rainbow of colours to represent a connection with all the elements. She believes her immersion in the spirit world helps her in her quest to cure patients with ancient knowledge and natural medicines.

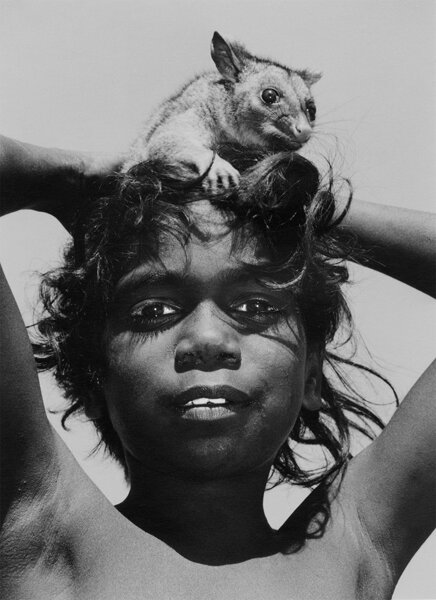

Voodoo plays a minor role in Santeria. On this earth the various Orishas have morphed into dolls, which are displayed by their owners to please the spirits. Such shrines are often prominent features in Cuban homes.

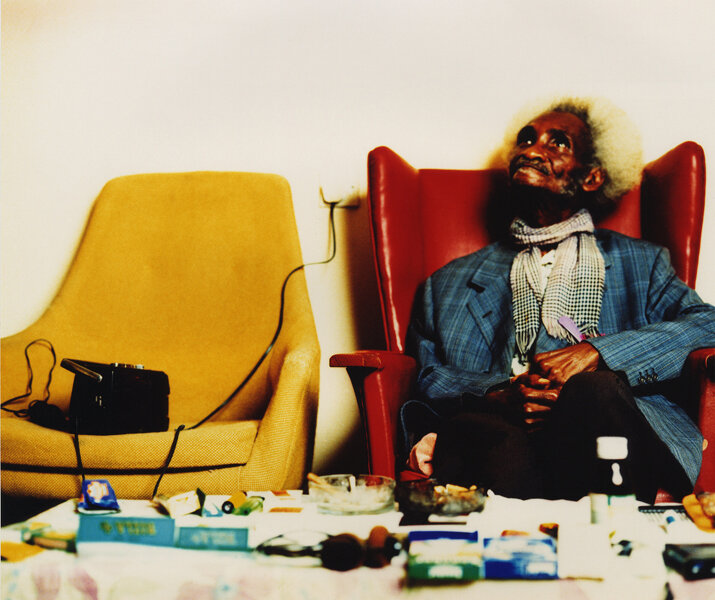

Made legendary in the West by Ry Cooder’s soulful documentary Buena Vista Social Club, Ibrahim Ferrer’s lace draped shrine to the Santeria gods is typical. Ferrer fed his gods rum and perfume to ensure they remained benevolent. If the gods are not kept happy, the Cuban misery maker can project bad luck and possible illness.

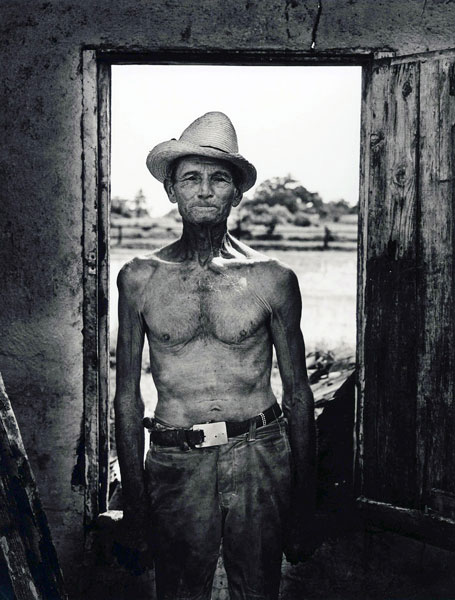

Those fearing impending sickness call on the services of their local Babalou (priest). These revered men are consulted for advice, for protection and when ill health threatens. The Babalou then consult’s the gods by way of stones draped in colourful beaded necklaces, which are placed in shrines and believed to be powerful. According to the Santero, these stones harbour the spirits of the Orishas, and spirits are as hungry as their mortal subjects. They need to be fed with food, herbs and even a drop of rum. During important ceremonies animal sacrifices are made, seasoning the dancing, singing and trances with blood.

The way of the Babalou is not open to your average Cuban man in the street. White clothing signals the aspiring Babalou’s commitment to serving the gods of Santeria, and must be worn to cleanse evil sins for one full year before initiation. The chosen few then partake in further ritual ceremonies. These might include being whipped by initiated Babalous as punishment for past sins and preparation for the hard path that is to come. New Babalous are showered with the coveted American dollar- but only after the greenbacks have had a good wash to rid them of negative connotations.

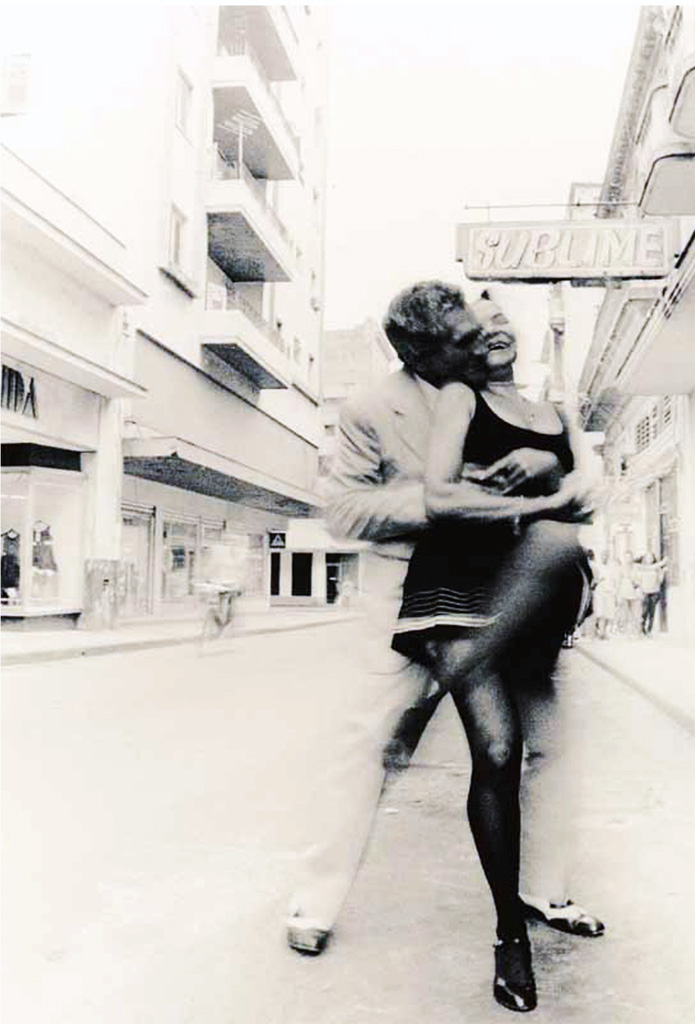

Cuban culture is saturated with Santeria and it’s widely believed that even Fidel Castro himself is not immune to the hold of the Orishas. Some believe Castro, a practicing Santero, to be the Son of Elegua-the god of destiny. As the ageing dictator rides out the last years of his regime, which must ultimately crumble when Castro’s bones turn to dust, will Elegua intercede to save his son and the impossible dream he had for Cuba?

‘Santeria De Cuba’, text by Lisa Wade (As published in Oyster magazine)